Kyzyl Kul

Kyzyl Kul |

In yesterday's session with calligraphy teacher Abdu-Shukkur we finally got around to crafting our own calligraphy pens. Making a calligraphy pen from scratch was much easier and took far less time than I had expected.

I have a couple books that give detailed directions as to how to make an Islamic calligraphy pen. Instructions from both books said to whittle one end of a dried reed into the form of a writing nib; for centuries this was the pen used by calligraphers across the Middle East. Abdu-Shukkur recommended bamboo as the best material, though I didn't know of anywhere near campus I could find wild bamboo. In making my first pen it somehow seemed apropriate to scavenge the raw material myself; I thought I knew a good place to find reeds.

So, a couple days before our calligraphy lesson, I strolled to Kyzyl Kul--a small lake on campus. I'd occasionally jogged around Kyzyl Kul with Paul after arriving in Urumqi over two years ago. I hadn't been by recently, but vaguely recalled seeing patches of rushes along Kyzyl Kul's southern edge. Pocketknife in hand, I set off to see if I could find something suitable for a calligraphy pen.

My recollection was correct... there were hundreds of reeds growing in the shallow waters. Many people were around the lake: fishing, chatting, or just enjoying the sunny weather. Unsurprisingly, nobody else seemed interested in harvesting reeds. I cut off the upper half of several tall stalks which grew close to the shoreline--I didn't even have to get my feet wet. I took the reeds back to my apartment, hoping that a couple days would be enough time for them to firm up.

Abdu-Shukkur and I wound up crafting calligraphy pens from four different materials: metal, wood, reeds, and bamboo. The simplest calligraphy pen to make was the one with a metal nib. All that one required was a cheap fountain pen and a pair of pliers with which to snip the nib. Pens used in Islamic calligraphy have a left-cut nib, cut along an angle of approximately 40 degrees. It takes about a minute to snip, then file down the end of an existing fountain pen.

Crafting the wooden pen took a little more time than transforming the fountain pen did. We used my pocketknife to sculpt and shape the ends of a couple slender branches into form. This required a bit more dexterity than merely snipping and filing down metal nibs. Still, it was surprisingly quick and easy.

Abdu-Shukkur with the 'Green Onion' Pen |

The metal and wooden pens both worked well, though my favorite had to be the one we crafted from bamboo. Neither Abdu-Shukkur nor I had brought any scraps of bamboo to work with, though eyeing my pen-case he saw one of the brushes I use for Chinese calligraphy. He idly mentioned that when he was young that the standard way to craft a pen for Islamic calligraphy was to take the bamboo stick of a Chinese calligraphy brush and whittle it into shape.

I proposed that we shape the unused end of one of my brushes, creating an implement that could be used for both Chinese brush calligraphy and Islamic calligraphy done with a pen. The results were excellent. I've found that I can write equally well with this homemade pen carved from bamboo as I can with a specialized metal-nib calligraphy pen, such as the Mijit Pen. The only drawback to the homemade pen is that I have to more frequently dip it into an inkwell to keep the letters flowing.

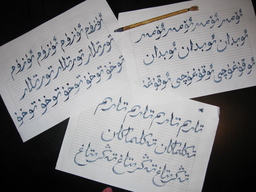

Double-Ended Brush/Pen with my Calligraphy Exercises |

Even the smallest Mom-&-Pop store still carries several different colors and brands of ink. Fountain pens and jars of ink cost roughly the same: between one and two yuan for either item, about 13¢ to 25¢ U.S.. However, with less demand for fountain pens, these materials are becoming harder to find. Abdu-Shukkur and I took our previous session scouring the art-supply shops of Urumqi, looking for cheap fountain pens to turn into calligraphy pens. We found the low end of the market is dropping out. Several times Abdu-Shukkur bemoaned this recent loss of abundant, cheap fountain pens. Most shops around town do continue to stock more expensive varieties of fountain pens, though I wonder if these pricier items aren't just leftover, unsold stock which nobody wants to buy.

I suppose the ready availability of pens is somewhat moot, now that I know how to make an excellent one for free out of bamboo. I'm sure that I won't still be living in China the day that none of the corner stores carry cheap india ink and leaky fountain pens. Still, it would make me happy to know that there remains some corner of the world where the necessary materials for both Chinese brush calligraphy and Islamic pen calligraphy are abundant and cheap. I felt Xinjiang to be unique in that regard, so find it sad to consider the decline of the only location I considered calligraphy nirvana.

Trivia: The broadcasting tower visible in the background of Kyzyl Kul is where Meengday delivers her Mongolian radio broadcasts.