Urdu Calligraphy

Urdu Calligraphy |

My past few days have been in Lahore, mostly visiting people I knew over the year I was studying Urdu here. So many folks are still around: Razzaq, the program director; Mushtaq, the cook; Junaid, the calligrapher.

I'm staying with a family in Lahore's old city--Razzaq arranged that for me. It's not free: I'll leave them 500 rupees per night, a little over $8 USD. Still, that amount is probably about what a mediocre hotel would cost in this city today. Additionally, those 500 rupees include breakfast and dinner: home-cooked. Spending time together with locals and having people who are excited to guide me around the city is invaluable. All the family members are welcoming and talkative, the food is good, and the conversation comfortable. Best of all, the adults are all calligraphers by profession. From what I understand, the patriarch--whom I presume has passed away, as he is never home--was a calligrapher. His sons and daughters all followed into the family trade.

Harmonium Player Old City, Lahore |

Leaving home each morning I walk together with Gudu, one of the family members. Gudu is one of the nicest guys I've met, in Pakistan or elsewhere. I'm guessing he's on one side or the other of 30, but don't ask. Inquiring about a person's age, religion, and marital status are all standard opening questions in this part of the world--it wouldn't be at all impolite to ask a pointed, "So, how old are you?", but I remain set in my ways. From home, we wind through the alleys, in ten minutes we find ourselves outside the old city. From the Lohari Gate it's minibus line 27 to Shadman Colony, where the Berkeley Urdu Language Programme Center is located. Gudu doesn't work in Shadman Colony itself, but is kind enough to see me off and stop in for a cup of tea at the program center. Gudu works in the next neighborhood over--Muslim Town--at the Government Office of Film. I'm not quite sure what that is, presuming it to be some sort of censorship board. Whatever their mission may be, his employee badge lists his position as "calligraphist"--which sounds super-cool to me.

Gudu, Dhaniya, & Mavra |

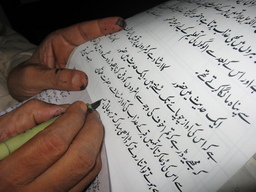

At the program center I hang out with the folks who are still around. The library is still there, and far improved from what it was in my day. The academic program structure is still in place, there are instructors hired on staff, even the very location is the same, in a residential area of Shadman Colony. But there are no students. The shell continues to operate in anticipation of the return of Urdu language students from the U.S., but it's been deemed too unsafe for any to come since September of 2001. It would be nice to sit in on language lessons, though with Junaid coming in daily I'm content. His calligraphy is the best I've actually seen somebody write, it's thrilling to sit alongside him and get pointers.

Junaid seems impressed with what I can do, showing what I write to Razzaq or anybody else who happens to be about. Perhaps he's going through polite motions, but I do detect an energy in his eyes as he nods his head, scrutinizing my work. Junaid offers me direction, and more so than I would get from Abdu-Shukur back up at Xinjiang University. "Think egg--not sun," Junaid tells me when writing a terminal letter jim. "The shape has to be tighter, truly ovoid: a 3.5 to 1.5 ratio. Tilted, like so..."

He's absolutely right, of course. If my calligraphy ever looks half as good as Junaid's calligraphy looks I'll consider myself accomplished.

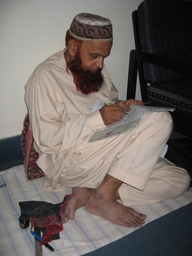

I ask Junaid about using computers for typesetting in Pakistan today. The default script used here is nastaliq which is far more ornate than naskh, the standard style in most countries which use the Arabic script. These days Junaid himself more often uses In Page, a software program from India, than doing work by hand. At the moment he does have a job scripting text out the traditional way, he's the scribe for a book soon to be published. At first I feel happy knowing that there is still a demand for such work. Then I feel conflicted. It is only because Pakistan is one of the world's poorest nations that people's time--even that of a master calligrapher--is worth pennies an hour.

Junaid at Work |

Certain things are different. Satellite TV from India is everywhere: India may be a conservative place by standards of the west, but what goes in films and TV serials from India today is risque by the standards of Pakistan. Shadman Colony now has a branch of Subway sandwiches, a chain which didn't exist in Pakistan when I lived here. Now that I think of it, I don't believe any western chains were in operation in this country then. I decided to sneak a half-sub in before returning to the old city this evening: I was surprised to find the staff employed both men and women. It was rare that I'd encounter women working outside of the home before. I certainly didn't expect to find teenaged girls in jeans and polo-shirts asking me to fill out their customer survey card rating my dining experience.

I'm mulling over my return to China. The Karakorum Highway is such slow-going that I think it will be better to break the journey into stages: seven hours by Daewoo bus to Abbottabad. One night in Abbottabad, followed by another day on the road, ending in Besham. The final stretch would take me to Gilgit. I'll probably linger in the Hunza Valley before crossing back up to Tashkorghan. I could leave tomorrow afternoon, after one last morning at the program center. But at the moment I'm thinking it will be good to draw out my return to Lahore, perhaps shopping around for ingredients hard to find back up in China.