A Western Mongolia Travelogue

BEIJING, China

BEIJING, China

December 22, 2006

I'm on my way back to the U.S. for a Christmas visit.

I arrived in Beijing yesterday morning on the T70 express train from Urumqi. I could have flown, but figured it was worth it to save a few hundred yuan. Savings aside, I love to travel by rail. There's something soothing about having, hours--days even--to spend before arriving at my destination.

I've been up and down the Urumqi/Beijing line enough times that the station names are all familiar and I have a good sense of the routine:

I make sure to not get caught needing to use the toilet while the train is in a station and the doors are locked. Reasonably priced hot meals are available from the dining car, though I usually bring ample provisions of my own. The layover time at some stations is a mere two minutes--not worth stretching my legs on those platforms. The longest wait time at any city will be eight minutes. Xi'an is one such stop, where I've made a certain ritual each time I pass through. I gaze out the window as the train pulls in at 10:00 P.M., admiring the city walls running parallel to the track. The layover is just long enough to step down to buy a bottle of the local brew--Hans--from a platform vendor, re-board, then start sipping as the train resumes its eastward journey.

I'm staying at Zach and Lisa's flat for a couple days before flying back to Seattle. Lisa herself left for a Christmas visit to Los Angeles on a flight yesterday evening: her first visit to America since moving to China last autumn. We were lucky enough to spend the afternoon together, chatting as she packed, before she had to rush off to the airport.

Today I'll be taking lunch with Joyce, then spending the evening with Zach. Tomorrow morning it will be a flight to Seattle, arriving back to the U.S. on the morning of Christmas Eve.

Below is the article I mentioned in my last entry. I took all of the photos, the staff at World Vision translated my English text into Chinese. It's not quite the same as flipping through, seeing images as half-page glossies. The beginning of the published version also included a route map of my path around Mongolia: I didn't create that one so can't provide an image.

Forewarning: long text, many photographs. Getting all the way through this one will take some time.

In summer of 2006 I travelled from China to Mongolia, then back again by land. Mongolia is unlike anywhere I have been.

That is not to exoticize the entire country. Walking down the streets of Ulaan Baatar will find sights similar to those seen anywhere across the globe: pedestrians, vehicle traffic, mobile phone stores, shops, and restaurants.

However, outside the capital, there is little about daily routine that will seem familiar to visitors from other countries. To a greater degree than anywhere else in the world, Mongolia has retained a traditional lifestyle. The majority of Mongolia's 2.5 million inhabitants still follow nomadic traditions. People move their homes in accordance with the seasons, grazing their animals in suitable pastures. Reliance upon land and animals is unrivaled.

But it's not merely Mongolia's vast, open landscape; the horsemen; or the nomadic lifestyle that make the country unique. There is something in the Mongolian mentality that is laid-back and casual in ways I seldom see elsewhere in the modern world. Social interaction across Mongolia is relaxed and full of smiles; time seems to simply not matter.

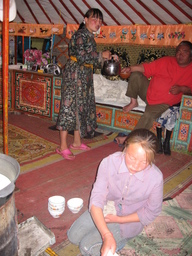

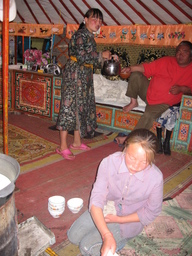

Even the most basic aspect of Mongolian life--the homes in which they choose to live, are a throwback to the dwellings of centuries past in most other countries. Rather than a fixed, built-up structure, most Mongolians choose to live in large, round, white tents, or ger. Insulated with felt and covered in canvas, gers are the ultimate mobile home. Crossbeams give the ger support; for a glorified tent, the interior of a Mongolian ger can be surprisingly cozy. Along with all of their livestock and any other possessions they may own, Mongolians move their ger around the land in accordance with the weather. This was traditionally done on horseback, though today it is common to see trucks and other motorized vehicles as part of the transportation process.

Me? I'm an American, I've spent my last two-and-a-half years as a foreign student in China. I live in Urumqi, studying at Xinjiang University. Over my time here I've taken every possible opportunity to explore the region and neighboring countries and provinces. Xinjiang itself shares a border of several thousand kilometers with Mongolia. Despite the proximity, everything I'd heard about Mongolia made it sound like a completely different world.

Getting to Mongolia from Urumqi is fairly straightforward. There are several border crossings open between Xinjiang and Mongolia. These entry points are restricted to local traffic: I wasn't sure whether I would be allowed to cross directly, traveling on a third-country passport. Additionally, I wanted to be sure to arrive in Ulaan Baatar in time for Mongolia's biggest holiday: the annual Naadam festival of traditional sports.

Rather than heading to the nearest border crossing (north from Urumqi to the Tashkent/Bulgan frontier) I decided to attempt a huge counter-clockwise circuit. Leaving Urumqi, I took trains east. This route brought me first to Jiayuguan in Gansu. From there I traveled onwards, spending a few nights visiting the capital of Chinese Inner-Mongolia, Hohhot. I finally made my way up to Ulaan Baatar via local train, changing at the border city of Erlian. My ultimate hope was to venture west across the country, returning to Urumqi by crossing the Xinjiang/Mongolia border, making the trip entirely overland.

The terrain of Mongolia is diverse, ranging from lush forests surrounding lakes to the arid emptiness of the Gobi desert. It would be impossible to see everything the country had to offer in one summer, so I had to choose from specific destinations when planning my route. In addition to getting to know Ulaan Baatar, my aim was to experience the natural beauty of Mongolia's two largest lakes: Lake Uvs and Lake Khatgal. Both lie in remote border areas of Mongolia's northwest, though they could not be more different from each other. Lake Uvs is a saltwater lake, far more saline than the ocean. Lake Khatgal is freshwater, supporting all manner of animal and plant life.

Even more so than visiting particular locations, I expected the travel and transport around Mongolia to be a unique experience. Covering this distance would require spending large amounts of time out in the pasturelands. It would be necessary to take my meals and spend my nights in the gers of nomadic herders.

I made this trip with a traveling companion from Urumqi, Meenday. Traveling together made getting around Mongolia far easier for me: Meenday is one of Xinjiang's ethnic Mongolian minority and fluent in the language.

Arriving in Ulaan Baatar after a 15-hour train trip from the border with China, my first impressions of Mongolia weren't that striking. I have visited several of the nations which were part of the Soviet Union over previous travels. Unsurprisingly, given Moscow's domination of Mongolia through the 20th century, I found Ulaan Baatar had a similar atmosphere: blocky apartment buildings, Cyrillic script, and decaying Russian-made vehicles gradually being replaced by more modern imports. Mongolia wasn't technically a part of the Soviet Union, but the control exercised from Moscow is still plainly evident in the buildings and streets of the capital.

Similar as the superficial elements of the city seemed to other places formerly Soviet, I could also sense something special in the pace and interactions with people. Namely, there was no sense of urgency in going about getting things done. Local Mongolians were relaxed, friendly, and open in a way that I found refreshing.

One of the most obvious differences I found was in how easily friends could be made. Most everywhere else I've traveled there is a need to engage in a specific banter upon meeting new people. It's a simple exchange common across the world, first establishing common ground and background before getting closer as friends. Upon meeting somebody new I'll typically be asked the same set of questions: "Which country are you from? How long have you been in our country? How do you like our country?" These opening questions are usually followed up with inquiries about occupation and family.

This process is common and natural across the world. Sharing and opening up is part of getting to know somebody, making chit-chat helps build up a closer relationship. What surprised me was how little of this routine needed to be carried out to get close to the people I met in Mongolia. I wound up spending hours--days even--together with people with whom I shared no common language, there was no sense of awkwardness or artificial attempts at communication. The Mongolians I met in both cities and countryside were immediately welcoming. Around Ulaan Baatar I spent days comfortably hanging out with people with whom I shared no common tongue. Nomads in remote pastures take in any traveler who happens by, providing tea, warmth, and shelter for a night. I spent many nights in some stranger's ger, being served milk tea and given blankets to keep me through the night.

Certainly, part of the reason it was so easy for me to get on easily without conversation was because I was traveling with a native Mongolian speaker who did much of the talking. Still, even after Meenday and I parted ways later in the journey, there was something immediate, genuine, and intimate in my interactions with locals. Long afternoons spent running errands, time spent sharing a meal, or hours going about seeing the city together were all full of laughter and ease. Even in Ulaan Baatar people seldom seemed pressed to go about things with any sense of urgency.

After spending a week in the capital making friends, attending the sporting events of the Naadam festival, visiting the monasteries, and seeing the sights of Ulaan Baatar, Meenday and I took a train north, to Mongolia's third-largest city, Erdenet. This train trip was to be our last comfortable journey in a month's travel around the country.

Travel by rail across Mongolia is not unlike travel by rail across China. It is possible to travel more comfortably by reserving a berth rather than a seat, at roughly twice the cost. The most expensive class of travel--equivalent to soft-sleeper--is rather nice in fact. These compartments of four berths also include a small video screen to watch closed-circuit programming.

Travel by rail across Mongolia is not unlike travel by rail across China. It is possible to travel more comfortably by reserving a berth rather than a seat, at roughly twice the cost. The most expensive class of travel--equivalent to soft-sleeper--is rather nice in fact. These compartments of four berths also include a small video screen to watch closed-circuit programming.

If it were possible to see much of the country by train, Mongolia would certainly be a far more popular destination than it is. Unfortunately, there aren't many places to go by rail around Mongolia. The entire country has only 1,810 kilometers of track laid, most of it cutting straight between Russia and China. The line we took out of Ulaan Baatar to Erdenet was a spur off of the main rail line connecting Beijing and Moscow. Aside from these train tracks and the paved streets of the larger cities, there is little vehicular transport infrastructure.

The railway serves only a small handful of destinations, getting from city to city usually requires travel by 4WD. The roads connecting destinations are by-and-large not projects planned by the government or constructed routes laid down by workers. Rather, cities are connected by scattered dirt tracks formed by the treads of previous vehicles. At any given point there may be three or four roads heading roughly in the same direction, occasionally running parallel, intersecting, or askew. Signs bearing directions might be found upon leaving a city, but nowhere for the hundreds of kilometers in between. I have many years of driving experience, but there is no way I would be able to find my way about Mongolia on my own.

Leaving Ulaan Baatar, the emptiness of the Mongolian countryside became immediate. Scattered yurts dotted the pastures and hills, thinning out with distance from the city. We specifically chose to leave Ulaan Baatar by train, knowing what transport options lay ahead across the rest of the country. Covering a distance of a couple hundred kilometers can take a full day--or two--in a Jeep, let alone the time spent waiting for a ride to turn up. Public buses are, for all practical purposes, non-existent. Paved roads do exist, though are found mostly within in Mongolia's few cities.

It's ironic that the Mongolian nation of today should have such poor infrastructure. Signs all over the country, especially during the festival of Naadam, proclaimed 2006 as the 800th anniversary of the Mongolian state established by Genghis Khan. It's impossible to describe Mongolian history in anything but superlatives, given the breadth of their empire, the organization of their army, and the advanced state of their infrastructure for centuries. During the 13th century there was no army superior--the Mongols were masters of archery, horsemanship, and military regiment. The Mongols once ruled the world, controlling an empire, the likes of which has never been equaled. Under the Mongols regions as far-flung as Baghdad, Moscow, Lhasa, and Guangzhou all answered to the Khans.

While the period of Mongolian history best-known in the west is undoubtedly this empire under the Khanates, the area has long been rich in human activity. The Xiongnu were among the first to engage China in battle, beginning in the 3rd century BC. The Uighurs dominated Mongolia until the year 840, when the Kyrgyz took control. They were in turn replaced by the Kitans from Dongbei, then briefly, the Chinese, before Genghis Khan built the Mongolian empire.

More recently, Mongolia was controlled by the Manchus: from 1691 until the collapse of their Qing Dynasty in 1911. Over the years of the Soviet Union's existence, Mongolia was essentially a satellite state. Local leadership and affairs operated hand-in-hand with Moscow.

At the end of our overnight train trip, Meenday and I found that the real journey had begun. Travel around the country is hard. In addition to the wretched state of roads around Mongolia, getting from place to place is not the straightforward matter it would be other parts of the world. We had little interest in lingering in the city we had just arrived, Erdenet. The city's one claim to fame was a colossal copper mine developed by the Russians in the days of Soviet influence. Our reason for stopping in Erdenet was merely its status as the furthest point west along the railway line.

Given Mongolia's scant transportation infrastructure, just getting a ride out of Erdenet was not that simple. We found a mud patch on the edge of town which served as makeshift bus depot. Asking around we found our options were limited: it was possible to find a ride back down to Ulaan Baatar, or out to the nearest towns to the west: Bulgan and Moron.

We were hoping to reach Moron, some 421 kilometers away. Traveling in most other countries, a distance that short could be covered in a matter of hours. In Mongolia, crossing a distance that great will take a number of days. We found an old van set to head to Moron in the early afternoon. It wasn't until a full day later, the subsequent afternoon, that we actually reached our destination.

There is a combination of reasons why travel around the country takes so much time:

First, outside of the capital, there is no system of tickets or timed departures. In theory, travelers show up where Jeeps congregate, a price and departure time are negotiated--hopefully everything works out. Just finding the ride can involve several days of waiting.

Second, the agreed-upon departure time will never be the actual time the vehicle leaves. Even if all the passengers have arrived, it will be some hours later that the vehicle actually moves anywhere.

Third, once the vehicle does leave, it will probably stop off several other destinations around town before hitting the open field. Occasionally these stops will be made in order to pick up other passengers, sometimes they are made to cram cargo into any open space within the vehicle. Filling the Jeep up is generally less a matter of transporting merchandise for sale as sending things to relatives or friends: an old television set, some plastic tubs, or perhaps a sack of potatoes.

Fourth, there is a probability that the vehicle will break down somewhere en route. Most of the vehicles plying the trails are in a some state of disrepair. Coupled with the remoteness and scarcity of parts, it's necessary to improvise when something goes out. These stops always add additional hours. Occasionally, breaking down will require waiting for a passing vehicle to provide tools, parts, or to take the passengers further toward their destination.

Fifth, Mongolians love to take breaks. Sometimes they don't even leave the vehicle to start drinking beer or vodka. Finishing off a bottle or two is a fine excuse to pull off the road and spend a stationary hour.

Finally, even if none of the above were issues, the roads are simply horrible. Driving along unmarked mud tracks is never a quick process. Even a new 4WD in proper condition would have to make its way slowly from point to point. Vehicles often have to wade through rivers that would be spanned by bridges in other countries. Heavy rains can mean an abrupt halt and long wait.

It took us over 20 hours to reach Moron from Erdenet. We knew in advance that the road would be poor and that it would take a long time to get from one city to the next. Why, rather than flying, did we choose this method of travel? Because bumping through the pastures is really the only way to experience Mongolia. The hours spent navigating open terrain impart a sense of how big and open the country is. Driving for hours finds endless rolling green hills and meadows. Where weather and terrain are fine, the traditional gers of Mongolian nomads punctuate the hills and pastures, other times it is possible to drive for long stretches without passing any sort of habitation, temporary or otherwise. The people remain nomadic, it's generally the exception to encounter any sort of fixed structure built from wood or brick. Mongolia is vast and open.

Driving along, suddenly--after miles of nothingness--there will be a glimpse into another civilization, another time. Encounters outside of the city will surely be unique. Some nomads open their gers up as simple restaurants, offering whatever food is available. Horseback riders in long, traditional robes (del) and American-style baseball caps gallop across the plains. Many of today's nomads do avail themselves of motorized transport, trucks and motorcycles are common sights. However, the horse is still central to life in Mongolia, for herding sheep, for transportation, and for travel.

Driving along, suddenly--after miles of nothingness--there will be a glimpse into another civilization, another time. Encounters outside of the city will surely be unique. Some nomads open their gers up as simple restaurants, offering whatever food is available. Horseback riders in long, traditional robes (del) and American-style baseball caps gallop across the plains. Many of today's nomads do avail themselves of motorized transport, trucks and motorcycles are common sights. However, the horse is still central to life in Mongolia, for herding sheep, for transportation, and for travel.

Fortunately for travelers both foreign and local, Mongolian hospitality is unrivaled. I have been to many welcoming lands, places where it's customary to offer passers-through a cup of tea, a meal, or a bed for the night. I've never been anywhere, other than Mongolia, where the expectation of anybody with shelter is that a traveling party of a dozen people might show up unannounced--at any hour--requesting a place to sleep and eat. Perhaps it's that the Mongolians have chosen a traditional existence over the trappings of development, or perhaps this welcoming openness is a necessary part of existing in a country with such a lack of infrastructure.

Accommodation is seldom luxuriant. The Mongol ger is little more than a large, round, tent with felt walls and canvas coating. As nomads, the Mongolians not only bring their possessions and livestock from place to place in time with the seasons, but this ger as well. Crossbeams with which to support the fabric of the ger and a central stove upon which to cook seem to be the only other material possessions universal to Mongolian nomadic life. However, I found it surprising how often we saw bulky items in gers that I would not have expected to find in land so remote. Tables, benches, carpets, shelves, and television sets were present more often than not in the gers we visited. It's also fairly common to see satellite dishes set up outside of gers, even in the most remote pastureland.

Finally making it to the city of Moron, we came one step closer to the first of the two lakes we hoped to visit: Lake Khovsgol. With 30,000 inhabitants, the city of Moron is one of Mongolia's few centers of population. As with the city of Erdenet, Meenday and I weren't interested in staying long in Moron. There are infrequent flights from Ulaan Baatar in the summer months. We could have flown in order to avoid the delays and discomfort of the Mongolian roads. However, piecing the journey together leg by leg afforded us glimpses into beautiful pastureland and Mongolian nomadic culture.

Lake Khovsgol lies in Mongolia's central north, 101 kilometers north of Moron. (As with all distances in Mongolia, the proximity can be deceptive. Even with ideal weather conditions and the best vehicle, those 101 kilometers take several hours to cover from Moron.) The freshwater lake practically bumps up to the border with Russian Siberia. The natural setting of all of Mongolia is beautiful, but Lake Khovsgol is a particularly pleasant place to visit for its scenery. There are forested hills running around the edge of the lake. Wild animals graze about the area, local nomads tend yak and reindeer around the lake.

Lake Khovsgol's surface area spans 136 km north/south, and 30 km east/west. It reaches a maximum depth of 262 meters and contains nearly 2% of the planet's freshwater supply. Fish thrive in Lake Khovsgol, the surrounding area supports a variety of wild animals and birdlife.

Even when the weather is poor, Khovsgol remains an attractive spot. Rain showers bring out the most beautiful rainbows, arcing across the meadows, into the forests and the lake. The southern edge finds a small village, Khatgal, with good resources to access the lake and enjoy the setting. Accommodation in Khatgal is plentiful and reasonably priced. It doesn't cost much to stay in either a traditional Mongol ger or a sturdy log cabin. Horses can be hired to make day trips to the lake, or a journey of several days up the shore.

Even when the weather is poor, Khovsgol remains an attractive spot. Rain showers bring out the most beautiful rainbows, arcing across the meadows, into the forests and the lake. The southern edge finds a small village, Khatgal, with good resources to access the lake and enjoy the setting. Accommodation in Khatgal is plentiful and reasonably priced. It doesn't cost much to stay in either a traditional Mongol ger or a sturdy log cabin. Horses can be hired to make day trips to the lake, or a journey of several days up the shore.

We passed several days visiting the lake and staying in Khatgal. It's easy to pass time wandering the meadows on foot or horseback, watching yaks graze, and sitting by the fire at night. The shoreline is accessible after passing through pleasantly wooded areas. Population tends to thin out farther up the lake from Khatgal, though.

After returning to Moron from Lake Khatgal it took three days to secure a ride onwards. In a land without timetables or tickets, how exactly do people arrange rides? Moron had improvised a fairly functional system of connecting people driving vehicles with passengers looking for lifts. A small shack held an old microphone and even older looking amplifier bearing Russian text. This set-up was connected to a loudspeaker above the edge of the bazaar, for a few tugrik it was possible to have the announcer state the destination and number of passengers.

Our destination was Ulaangom in Uvs province, in Mongolia's far west. Ulaangom is a mere 680 kilometers from Moron, but covering that much distance in Mongolia can be like asking for a ticket to the moon. Few vehicles head west from Moron, those that were going that direction were off to cities much closer to Moron.

So, while waiting, we got to know the city of Moron a bit. As with most everybody around Mongolia, the announcer for rides was friendly and welcoming, inviting us into her apartment and helping us to find a place to stay.

I suppose it's unfair to say that travel around Mongolia is necessarily slow and fraught with delay. As with most parts of the world, paying enough could buy what you want with immediacy. Jeeps were available, we were offered a ride in a nice 4WD almost immediately upon returning to Moron from Khatgal. However, the asking price was 300,000 tugrik, about $235 U.S.. Rather than charter a sturdy new vehicle, we were hoping to travel as the locals did. This would mean a fare closer to $25 each.

Over the days we waited for a lift to turn up, we came to experience life typical to a small Mongolian city. It was in Moron where we became familiar with the limited range of food comprising Mongolian cuisine. We had been spoiled by staying our first week in Mongolia in Ulaan Baatar, where a great variety of food can be found. As Mongolia's capital and largest city, Ulaan Baatar had a fair selection of various cuisines on offer: imported foodstuffs in well-stocked supermarkets, and a broad list of choices on restaurant menus. In much smaller Moron (population 30,000), as elsewhere across the country, the restaurants tended to offer very little variety.

The staple dish across the country is mutton. In Mongolia there are various ways to prepare mutton, the names of some of the most common items are related to the names of similar dishes in Russian and Chinese cuisine: buuz, goulash, beefsteak, and cutlet.

Buuz was by far the dish we found most commonly available across Mongolia. Cognate to the Chinese bao zi, buuz are thick mutton dumplings boiled up with a thin, outer skin of dough. Buuz tend to have little more than mutton inside, though with luck there may bits of onion or another vegetable cut in.

Even though each dish had a different name, I found it difficult to distinguish between the other three most commonly available dishes: goulash, beefsteak, and cutlet. They were all essentially just mutton cut to various sizes: mutton minced finely, mutton cut into pieces, or mutton served as a large slice. The meat would be smothered in a brown sauce and served with some sort of starch accompaniment, mashed potatoes or a bed of rice. A garnish of pickled vegetables or salad made from cucumber and tomato would occasionally serve as side dishes.

Outside of the city there were only two other Mongolian dishes which I encountered with any frequency, though these were less common than the four dishes I mention above. Khushuur, a flat, oily cake of dough with bits of mutton inside was occasionally the meal of the day. I was surprised to be served fresh noodle dishes at a couple of the remote gers I stopped at. I didn't see anybody inside pulling dough, so paid close attention to the preparation process the next time it was served. I found that these noodles were cut, formed by finely slicing a large piece of flatbread into strips.

Outside of the city there were only two other Mongolian dishes which I encountered with any frequency, though these were less common than the four dishes I mention above. Khushuur, a flat, oily cake of dough with bits of mutton inside was occasionally the meal of the day. I was surprised to be served fresh noodle dishes at a couple of the remote gers I stopped at. I didn't see anybody inside pulling dough, so paid close attention to the preparation process the next time it was served. I found that these noodles were cut, formed by finely slicing a large piece of flatbread into strips.

Whatever dishes might potentially exist in Mongolia--even printed on a restaurant menu--is something of a moot point. Eateries in cities other than Ulaan Baatar will likely find just one or two dishes actually available, despite extensive menu listings. Out in the countryside, dining is a matter of eating what food you are served, not choosing between various options.

Strangely, given the lack of variety in Mongolian cuisine, condiment sauces are integral to the Mongolian dining table. I was surprised to find that every tabletop in Ulaan Baatar, every remote restaurant (which in Mongolia go by the Chinese name guanz,) and every ger miles from nowhere had two bottles: one of ketchup, one of a salty sauce from Poland similar to soy sauce. Mongolians douse each meal with liberal spurts from either bottle.

After waiting three days and sampling mutton prepared in every conceivable manner, Meenday and I finally got a lift out of Moron. Biding our time paid off. We managed to get a ride with two men driving a Jeep back to their home in Uvs province, the province of which Ulaangom is the capital city. Rides in Mongolia generally charge passengers double-fare to their destination in the event that they can't find a a paying passenger for the return trip. We were lucky: not many vehicles head all the way west to Uvs but that day there was a Jeep returning. This meant we were offered an inexpensive fare straightaway: 50,000 tugrik for the both of us. Again, a journey of a few hundred kilometers took several days, owing to the lean infrastructure of the road network.

Along the tracks heading to Uvs we encountered another traveler: a 76 year-old man driving alone, returning to his home in western Mongolia. He was having a bit of difficulty being sure which track to take, so we agreed to travel together, both his Jeep and ours in tandem. I have to say that I was mightily impressed with this character, driving alone in one of the world's remotest areas, in an old, unreliable, Russian-made 4WD. Typical with travel around the country there were frequent delays: problems with his vehicle, problems finding the way, or just a lack of ability to navigate the terrain. However, never did the breakdowns or bad roads seem to annoy anybody. Mongolians have to be some of the most laid-back, patient people I've met.

On the first evening of our journey from Moron we twice encountered streams so swollen with rain that passing them was an uncertain prospect. Both times we merely waited for a vehicle to approach from the opposite bank to see whether it would choose to cross. Given the lack of traffic, waiting for another Jeep or van meant a stall of nearly an hour, but it also meant that we didn't have to risk driving our own vehicle into the river and getting stuck ourselves. I'm not sure what we would have done had the traffic from the opposite bank decided to use the same strategy.

Occasionally we made our stops for other reasons. Spread along the Mongolian roadsides are ovoo, mounds of stones and other objects gathered into a peak. On top of, or next to this mound of stones will often be a framework of tree branches intersecting at a central point around which flags and fragments of cloth are draped. These ovoos are shrines of Mongolia's main religion: Buddhism. Mongolians follow the same school of Buddhism found in Tibet, observing the same hierarchy of lamas and reincarnation. The chanting, candles, robes, and iconography are all identical to those seen around the monasteries of Lhasa.

It is customary in Mongolia to stop when encountering an ovoo, then get out and walk around its base at least once. Buddhist ritual affords special significance to carrying out acts in certain numbers of repetition, the number three being the lowest number of iterations with higher meaning. So, more often than not, we would stop the Jeeps at an ovoo, get out, and walk its circumference three times. On occasion the ritual involved sharing a bottle of vodka and flicking the alcohol onto the mound.

These ovoos are often built on high ground, on hilltops and other points of higher altitude. When approaching an ovoo it is traditional to bring something up from down below to add to the mound. This object might be another stone, an empty bottle, a ceramic cup, or some fabric to drape across the mound. Animal skulls and crutches are often thrown on as well.

After sunset, we stopped at the first settlement we came across. Rather than the typical ger, we found an actual wooden house built-up not far from the river we had just crossed. The Mongolian family living inside took us all in without question. They had little to share in the way of food, though were generous in pouring us cups of milk tea. Fortunately we had brought some packages of instant noodles and canned food, so didn't go hungry that night. We sat around a long wooden table, candles providing the only illumination. After finishing our basic meal our hosts laid out padding and blankets upon the platform on which they normally would have slept.

I'm not sure which was more striking about the experience--staying out in the pastureland in a location so remote, simple, and beautiful, or the ease with which we were taken in. There was no expectation of compensation or payment, there was nothing at all strange in our barging in and expecting to be hosted. Indeed, several hours later, another group of local Mongolian travelers arrived. We just squeezed together on the platform to accommodate the new arrivals. There were at least ten guests crowding into the simple shack but no question at all about receiving unannounced visitors.

Departure the next morning was simple enough. We merely got out of bed and left the house before our hosts woke up. No formalities, no elaborate "thank-yous" to our hosts, no long goodbyes.

We were lucky to have met the elderly man driving his clunky Jeep. He was willing to take us even farther than the ride we had arranged back in Moron. He took us all the way to Ulaangom, stay for a few days, then down to the city of Khovd, not far from a border crossing with Xinjiang.

Relative to some of Mongolia's other cities, Ulaangom had a relatively decent infrastructure. Our time in Moron saw how limiting isolation and lack of roads can be: Moron's central streets weren't even paved. We had found that Erdenet was blessed with status as a spur off of the Trans-Siberian railway line, allowing for goods and basic infrastructure. Being far from the railway, I hadn't expected a similar situation in Ulaangom, so was pleased to find it a bit more built-up. I found the reason for it's fair infrastructure is that the Russians built a good road connecting Ulaangom.

So, in contrast to the limited fare and spartan infrastructure we found in Moron, Ulaangom was a relatively pleasant place to spend a few days. What makes Mongolia such a unique destination is the nomadic life found in the remote areas we had just driven through. However, it was refreshing to be somewhere with showers available and real beds. Meenday had local friends in Ulaangom who helped us find accommodation in a comfortable hotel. The shops were stocked with goods from Russia, there were even restaurants with dishes other than buuz and goulash available.

While Ulaangom was a comfortable, small city to pass time in, experiencing the best of what Mongolia has to offer involves spending time outdoors. We hired a Jeep to take us to nearby Lake Uvs, Mongolia's largest lake, covering an area of 3423 km sq. Upon reaching Lake Uvs, I again found the typical Mongolian approach to enjoying life: we stripped down to our underwear and went swimming. Our group was a mixture of both women and men, but nobody seemed overly concerned with modesty or the fact that we were laughing and splashing around in our underwear. Time and again across the country I noticed this relaxed approach to life Mongolians seem to have.

While Ulaangom was a comfortable, small city to pass time in, experiencing the best of what Mongolia has to offer involves spending time outdoors. We hired a Jeep to take us to nearby Lake Uvs, Mongolia's largest lake, covering an area of 3423 km sq. Upon reaching Lake Uvs, I again found the typical Mongolian approach to enjoying life: we stripped down to our underwear and went swimming. Our group was a mixture of both women and men, but nobody seemed overly concerned with modesty or the fact that we were laughing and splashing around in our underwear. Time and again across the country I noticed this relaxed approach to life Mongolians seem to have.

In addition to being a fine place to swim, Lake Uvs was also the site of my most interesting meal in Mongolia: khorkhog. The ingredients going into our khorkhog were fairly simple: water, mutton, and a few wild spring onions. What made the dish unique was its unusual cooking method: everything was placed inside a large metal canister resting on a few burning logs. Before starting the fire, people hunted around for stones of a particular size and heft, to place beneath the burning logs.

After the fire had been burning for a short while, the stones were taken from beneath the fire and placed inside the pot itself. The idea was to cook the meal more fully, adding a heat source from within. After opening the pot up, we used large knives to hack meat off of the bones--for such simple ingredients the meal was absolutely delicious. Before beginning our meal, the stones--now greasy, but still quite hot--were removed and passed around. The ritual seemed to be to hold one for as long as possible before passing it into another hand or passing it off to another person. The local Mongolians claimed this would somehow be beneficial for blood circulation.

After finishing our meal, I was impressed with the respect with which we cleaned up after ourselves once the lakeshore visit was over. Waste was collected, then either immediately burnt, or brought back into town to be disposed of later. Over the weeks making my way across the country I had noticed that the roads and pastures of Mongolia were largely free of trash and empty packaging. I had presumed this was solely on account of the thin population and traditional lifestyle, but was pleased to see that the Mongolians gave deliberate thought to keeping their country beautiful, maintaining a clean, litter-free environment.

After finishing our meal, I was impressed with the respect with which we cleaned up after ourselves once the lakeshore visit was over. Waste was collected, then either immediately burnt, or brought back into town to be disposed of later. Over the weeks making my way across the country I had noticed that the roads and pastures of Mongolia were largely free of trash and empty packaging. I had presumed this was solely on account of the thin population and traditional lifestyle, but was pleased to see that the Mongolians gave deliberate thought to keeping their country beautiful, maintaining a clean, litter-free environment.

After several days in Ulaangom we continued southwards with the old driver down to Khovd, his hometown. Khovd was to be our last stop before arriving at the Xinjiang/Mongolia border. Khovd is a rather small city, but does boast one of Mongolia's few universities. It also has quite a history, being one of the areas from which the Manchus ruled during the Qing dynasty. As with most of our travel to cities around Mongolia, the cities themselves were not the attraction, but rather a point from which to explore other areas. We did take in Khovd's central bazaar, which had products almost exclusively from Russia and China.

Our arrival in Khovd was well-timed. Upon arrival, our first item of business was arranging onward transportation. We inquired at the local bazaar and found that there were several other travelers hoping to get a ride to the China border. We had enough people to charter a Furman, an old Russian-made van. The price was right, at 15,000 tugrik per traveler. Even better, the travelers had already found a driver with a vehicle and were hoping to set off that very evening.

We took lunch and explored the city of Khovd, then waited at our departure point, the gate to the bazaar. Nobody else arrived for nearly an hour. We tried calling the driver on his mobile phone to be sure we hadn't made a mistake in location or time. No, we hadn't made a mistake--they were "on their way" the driver replied. No road trip in Mongolia starts off on time.

Again, typical with travel across Mongolia, a distance of a few hundred kilometers took over a day to traverse. The slow pace allowed us to see more of the terrain: we were gradually arriving in land more similar to the deserts of Xinjiang.

In Mongolia's far west there are people of many different minority ethnicities, the largest of them being Kazak. The van broke down entirely, giving us an extra night in the countryside. We spent time drinking tea in gers, chatting with local yak herders who spoke Kazak and Mongolian, and wandering the hills.

In Mongolia's far west there are people of many different minority ethnicities, the largest of them being Kazak. The van broke down entirely, giving us an extra night in the countryside. We spent time drinking tea in gers, chatting with local yak herders who spoke Kazak and Mongolian, and wandering the hills.

When we were 60 kilometers from the border, the unexpected happened: we arrived at a wonderfully paved road. Chinese road crews are working on a project to extend the road from the border, all the way through Bulgan and up to the town of Khovd. It was the best road I'd been on in all of Mongolia. It surely would have been many more hours of bumping through the dirt to go this last distance, instead it took far under an hour.

The Tashkent/Bulgan border crossing is open, but I'd heard that it was only to people with Mongolian or Chinese passports. I figured there was a chance the regulations could have changed, or that the border guards wouldn't really care, given the remote location. However, I was firmly denied passage by the head official, so had to part ways with Meenday. She continued on back to Xinjiang, I had to turn around a head back north.

Despite refusing my exit, the officials were friendly and talkative. The customs inspector spoke the best English and allowed me to accompany her on inspections of vehicles entering China. Her straightforward opinion was that most stuff coming up from China was "junk"--based on what I saw coming in, I had to agree. It seemed like people were bringing back the lowest-quality of merchandise, much of it not even new. The main job of the customs inspector was to levy duties, she said that she rarely did. Making her job even easier, going the opposite direction, the beds of the trucks leaving Mongolia were empty, clearly heading down to China to bring merchandise back up. One truck did have a pile of sheepskins and a few stray aluminum cans, Mongolia does not have a lot available for export.

By evening the border officials had helped me arrange the next leg of my journey. That evening a caravan of traders had crossed in from Xinjiang, driving up to the far western city of Olgii. Olgii is a small, mostly Kazak city in Mongolia's far west. Riding in a convoy of several trucks with these Kazak traders returning from China, I had some of my most intriguing interactions and experiences of the journey.

Though the ethnic Kazaks of Mongolia represent only 5% of the country's total population, they form the majority in Mongolia's westernmost aimag (province) of Bayan-Olgii. As with the ethnic Mongolians who form the the country's majority, the local population of Kazaks have maintained a traditional nomadic existence. Much of their present lifestyle is similar to that led by the greater Mongolian population: a nomadic existence revolving around moving gers in accordance with seasonal changes.

Though the Kazaks I met around western Mongolia were as equally open, friendly, and laid-back as the Mongolians I met back east, there are fundamental differences between the two societies. The most basic is religion: Kazaks are overwhelmingly Muslim. As with the Mongolians, mutton is the most common item at mealtime, though Kazaks are happy to eat dishes the ethnic Mongolians will not touch (such as horse sausage). As Muslims the Kazaks naturally shun pork, which, while not a common item, is a food that Mongolians will eat. Import shops will occasionally find the stray salami from Russia.

Having traveled around the fringes of Xinjiang I thought I had a sense of Kazak culture and how it varied across the borders. The countries with the largest numbers of ethnic Kazak residents are Kazakhstan, Mongolia, and China.

Decades as a part of the Soviet Union left a huge mark on the Kazak population in what is now independent Kazakhstan. The Alma-Ata of today is an overwhelmingly European city, many of the ethnic Kazaks residing in Kazakhstan have superior ability in the Russian language over Kazak.

Having also seen the nomadic Kazak populations living around Xinjiang I thought that it was perhaps in China the traditional Kazak lifestyle had been best maintained. It wasn't until exploring these reaches of western Mongolia that I came to find traditional Kazak culture has been best preserved in Mongolia. I found traditions still observed in Mongolia unknown to Kazaks living in either China or Kazakhstan. For example, Kazaks in Mongolia will not cut a boy's hair until his ninth birthday. Xinjiang Kazaks, on the other hand, follow the Chinese custom of shaving a young child's head, in the false belief it will encourage hair growth.

I found my days leaving the Xinjiang/Mongolia border to be the hardest travel I have ever done. It took three days and two nights to cover 500 kilometers in a convoy of trucks. The Kazak traders I was riding along with kept repeating, "This road is the worst road in the world". They weren't joking. I doubt they had seen many other roads by comparison, but I had to concur. I've never made such slow time traveling anywhere else.

Our route was to take us from the Tashkent/Bulgan border crossing up to Olgii. Meenday, traveling on a Chinese passport, had been permitted to cross back into Xinjiang. Her absence made the logistics more difficult, but also meant for a more rewarding travel experience. I was on my own to interact and connect with the people.

In a sense this was the best part of the country for Meenday and I to part ways. Over my time in Xinjiang I've studied the Uighur language. Both Uighur and Kazak belong to the Turkic language family. This meant that with patience we could communicate. I spoke in Uighur, they spoke in Kazakh. Despite being on my own, I could express my needs and understand a fair amount of what was being said to me.

Despite the difference in religion, diet, clothing, and language, the Kazak people I met shared the equally laid-back, easy-going approach to life I loved in the Mongolians back east. Riding with these traders got me through some of the most beautiful parts of Mongolia and connected me to a culture that is remote and traditional. Slowly making our way from the border with China saw terrain similar to the deserts of Xinjiang. The Altay mountains do not reach terribly high, but are beautiful nonetheless. The peak of Nayramadlin Orgil in this range gives Mongolia it's highest point of elevation at 4374 meters.

Leaving from the border was not a problem. China has paved a road all the way from the border through Bulgan. At the time it extended well past the city, 60 kilometers into Mongolia. However, we turned off the paved road only 15 kilometers along, taking the old trails directly up to Olgii. Most trucks and Jeeps that came up from China that day left together in the early evening, forming a loose convoy. We wound up sticking closest with two other trucks, arriving at a camp of several gers sometime after sundown and spending the night.

I found that how well I could communicate with my new travel companions depended entirely upon how much effort we both put into trying. Of the men in the convoy, one--Erken--was clearly the leader. Even without the advantage of some mutual Uighur/Kazak intelligibility, I think we would have gotten along well anyway. He tried hard to understand what I had to say and would speak slowly in response. Occasionally he would render my Uighur into proper Kazakh for the benefit of the others in the traveling party. I found it amusing that he could understand what I had to say but had to rephrase it for the others who did not want to take the effort to do so themselves.

As with most of the meals I ate around Mongolia, the Kazaks' main dish was also mutton. Having seen mutton served in every conceivable form across the rest of Mongolia, I didn't expect that I could be served anything new. Our first night staying in a Kazak ger proved me wrong, as the opening appetizer was nothing more than a plate of bare sheep shanks. All meat had been boiled off and was being prepared separately, leaving nothing of substance to eat. Nevertheless, a large platter of bones was presented to us to begin gnawing on before the actual meal.

That night in the ger was one of the most comfortable I've slept. From the outside, a ger (called kigiz ui in Kazakh) appears tiny. Once inside, it feels spacious and cozy. Mats and pads spread around the ground make for comfortable bedding. A central hearth provides not just a stove on which to cook, but warmth through cold nights.

We rose early the next morning, waking at 6:30 to get an early start on the day. Over this first full day of travel our convoy of large cargo trucks covered little over 100 kilometers. I'm sure that 4WD vehicles could have covered ground somewhat more quickly, though the 500 km from Xinjiang border to the city of Olgii must be a multi-day journey for anybody who attempts it, given the state of the roads. The terrain of Bayan-Olgii aimag and all of western Mongolia may be mountainous and rough, but it's more an absence of infrastructure than impassable terrain that makes travel so slow.

Creeping along over several days and nights on the road, I continually found that Mongolia's western Kazak population is equally laid-back, easy-going, and casual as the majority Mongolian population. Our vehicles broke down frequently, but these moments were seen as an opportunity to get out of the trucks for awhile and pause for tea. I found the greatest difference in outlook came on the last day on the road, when we were within distance of our destination of the city of Olgii. It was this last day that best typified my sense of what makes Mongolia unique, a special place from another time. Yes, Mongolia still has riders herding sheep on horseback, nomads packing tents across pasturelands, and so many other traditions that have died out most of the rest of the world. However, there's something in the outlook, the ability to accept and enjoy life, transforming an otherwise arduous experience into a day of laughter and enjoyment.

Just what was the cargo of our caravan? Traveling from Xinjiang across some of the worlds most difficult roads, I'd like to pretend that such a trip was carrying exotic goods, perhaps spices and fabric as in the days of the old Silk Road. However, peeping into the beds of several of the trucks revealed objects of the most ordinary nature: Fluorescent light tubes. Tires. Hundreds of vacuum flasks. Cheaply made clothing. Rather than tea and silk, mundane household items are the goods which China exports to the world today. And these merchants, like those who plied the Silk Road in days past, were of course trading only in items for where there would be both demand and profit.

By morning of our third day traveling together, the road was improved--we could have arrived in Olgii by early afternoon. Instead, we came into town at nightfall, many hours later. The reason for this was solely because the Kazak traders decided to enjoy themselves. Despite the difficult road, despite the lack of facilities, despite the long journey from Xinjiang, everybody decided to make the most of the last day and stretch it out as long as possible.

Personally, my feeling at the end of a long road trip is that once my destination is in sight, it makes sense to press on a little more than I normally would, to finish things off. Everybody else in the convoy had the opposite idea.

We pulled over to take lunch in Tolbo, a small city just over an hour away from our destination, Olgii. I knew that we were close to Olgii, and would have pushed on for a late lunch in Olgii rather than stop in Tolbo. I accepted that being lunchtime it was reasonable enough to stop--I was hungry too.

After finishing lunch, we drove out of town, then immediately doubled-back. The driver of the truck I was riding in saw somebody familiar driving in the opposite direction. Both drivers decided to head back into town to share a few cans of beer. After lingering over the beer, our truck made it ten minutes out of town before coming across the rest of the convoy, who had also decided to take a beer break. We joined them and drank yet more beer.

After finishing the second beer break, we drove on. We traveled for the better part of hour, when we happened upon some other vehicles from a different convoy of traders. This was deemed occasion for everybody to halt their vehicles and drink a bottle of Russian vodka. After the vodka, we finished a bottle of of Chinese bai jiu.

Two empty bottles and another hour later, we got on the road again. After a few minutes we came across a river. We again stopped, the men in the convoy waded in the shallow parts of the stream for 40 minutes.

When everybody had finished wading, we took off again. Not five minutes later everybody pulled off the road to get out, finish off all remaining beer and sing together. Everybody seemed to know all the words, and nobody was shy to belt out traditional Kazak songs.

There were two more stops on the way to Olgii, one to assist with a van that had broken down, the second for no apparent reason after we'd crossed a checkpoint upon reaching the outskirts of the city.

I initially was frustrated: we could have reached our destination hours ago. After being grumpy for awhile, my attitude changed. I realized that this was what was unique about the country, setting the peoples of Mongolia apart from so many others. The slow, easy-going lifestyle was chosen and deliberate. Everybody else was having fun, doing everything they could to extend a trip they were enjoying. Why was I the only one in such a hurry?

People in Mongolia today could move to cities, chosing a permanently settled existence, but most opt for nomadism. Why? Because they prefer to live that way. These traders driving goods up from China could have hurried on to their destination to save a day, but chose not to. Why? Because they were having fun.

With our arrival in Olgii my cross-country Mongolia adventure came to an end. I hadn't been allowed to cross the border back into Xinjiang, though had made it all the way across Mongolia to it's far west. Olgii had a small airstrip with flights back to Ulaan Baatar. I debated making my way overland back to Ulaan Baatar in another Jeep or other land vehicle. I could see more, it would be far cheaper... Still, despite feeling that "the only way to travel around Mongolia was by land" I'd seen enough. I booked a flight to the capital, from where I took a cozy train down to Beijing.

Travel by rail across Mongolia is not unlike travel by rail across China. It is possible to travel more comfortably by reserving a berth rather than a seat, at roughly twice the cost. The most expensive class of travel--equivalent to soft-sleeper--is rather nice in fact. These compartments of four berths also include a small video screen to watch closed-circuit programming.

Travel by rail across Mongolia is not unlike travel by rail across China. It is possible to travel more comfortably by reserving a berth rather than a seat, at roughly twice the cost. The most expensive class of travel--equivalent to soft-sleeper--is rather nice in fact. These compartments of four berths also include a small video screen to watch closed-circuit programming.

BEIJING, China

BEIJING, China

Driving along, suddenly--after miles of nothingness--there will be a glimpse into another civilization, another time. Encounters outside of the city will surely be unique. Some nomads open their gers up as simple restaurants, offering whatever food is available. Horseback riders in long, traditional robes (del) and American-style baseball caps gallop across the plains. Many of today's nomads do avail themselves of motorized transport, trucks and motorcycles are common sights. However, the horse is still central to life in Mongolia, for herding sheep, for transportation, and for travel.

Driving along, suddenly--after miles of nothingness--there will be a glimpse into another civilization, another time. Encounters outside of the city will surely be unique. Some nomads open their gers up as simple restaurants, offering whatever food is available. Horseback riders in long, traditional robes (del) and American-style baseball caps gallop across the plains. Many of today's nomads do avail themselves of motorized transport, trucks and motorcycles are common sights. However, the horse is still central to life in Mongolia, for herding sheep, for transportation, and for travel.

Even when the weather is poor, Khovsgol remains an attractive spot. Rain showers bring out the most beautiful rainbows, arcing across the meadows, into the forests and the lake. The southern edge finds a small village, Khatgal, with good resources to access the lake and enjoy the setting. Accommodation in Khatgal is plentiful and reasonably priced. It doesn't cost much to stay in either a traditional Mongol ger or a sturdy log cabin. Horses can be hired to make day trips to the lake, or a journey of several days up the shore.

Even when the weather is poor, Khovsgol remains an attractive spot. Rain showers bring out the most beautiful rainbows, arcing across the meadows, into the forests and the lake. The southern edge finds a small village, Khatgal, with good resources to access the lake and enjoy the setting. Accommodation in Khatgal is plentiful and reasonably priced. It doesn't cost much to stay in either a traditional Mongol ger or a sturdy log cabin. Horses can be hired to make day trips to the lake, or a journey of several days up the shore.

Outside of the city there were only two other Mongolian dishes which I encountered with any frequency, though these were less common than the four dishes I mention above. Khushuur, a flat, oily cake of dough with bits of mutton inside was occasionally the meal of the day. I was surprised to be served fresh noodle dishes at a couple of the remote gers I stopped at. I didn't see anybody inside pulling dough, so paid close attention to the preparation process the next time it was served. I found that these noodles were cut, formed by finely slicing a large piece of flatbread into strips.

Outside of the city there were only two other Mongolian dishes which I encountered with any frequency, though these were less common than the four dishes I mention above. Khushuur, a flat, oily cake of dough with bits of mutton inside was occasionally the meal of the day. I was surprised to be served fresh noodle dishes at a couple of the remote gers I stopped at. I didn't see anybody inside pulling dough, so paid close attention to the preparation process the next time it was served. I found that these noodles were cut, formed by finely slicing a large piece of flatbread into strips.

While Ulaangom was a comfortable, small city to pass time in, experiencing the best of what Mongolia has to offer involves spending time outdoors. We hired a Jeep to take us to nearby Lake Uvs, Mongolia's largest lake, covering an area of 3423 km sq. Upon reaching Lake Uvs, I again found the typical Mongolian approach to enjoying life: we stripped down to our underwear and went swimming. Our group was a mixture of both women and men, but nobody seemed overly concerned with modesty or the fact that we were laughing and splashing around in our underwear. Time and again across the country I noticed this relaxed approach to life Mongolians seem to have.

While Ulaangom was a comfortable, small city to pass time in, experiencing the best of what Mongolia has to offer involves spending time outdoors. We hired a Jeep to take us to nearby Lake Uvs, Mongolia's largest lake, covering an area of 3423 km sq. Upon reaching Lake Uvs, I again found the typical Mongolian approach to enjoying life: we stripped down to our underwear and went swimming. Our group was a mixture of both women and men, but nobody seemed overly concerned with modesty or the fact that we were laughing and splashing around in our underwear. Time and again across the country I noticed this relaxed approach to life Mongolians seem to have.

After finishing our meal, I was impressed with the respect with which we cleaned up after ourselves once the lakeshore visit was over. Waste was collected, then either immediately burnt, or brought back into town to be disposed of later. Over the weeks making my way across the country I had noticed that the roads and pastures of Mongolia were largely free of trash and empty packaging. I had presumed this was solely on account of the thin population and traditional lifestyle, but was pleased to see that the Mongolians gave deliberate thought to keeping their country beautiful, maintaining a clean, litter-free environment.

After finishing our meal, I was impressed with the respect with which we cleaned up after ourselves once the lakeshore visit was over. Waste was collected, then either immediately burnt, or brought back into town to be disposed of later. Over the weeks making my way across the country I had noticed that the roads and pastures of Mongolia were largely free of trash and empty packaging. I had presumed this was solely on account of the thin population and traditional lifestyle, but was pleased to see that the Mongolians gave deliberate thought to keeping their country beautiful, maintaining a clean, litter-free environment.

In Mongolia's far west there are people of many different minority ethnicities, the largest of them being Kazak. The van broke down entirely, giving us an extra night in the countryside. We spent time drinking tea in gers, chatting with local yak herders who spoke Kazak and Mongolian, and wandering the hills.

In Mongolia's far west there are people of many different minority ethnicities, the largest of them being Kazak. The van broke down entirely, giving us an extra night in the countryside. We spent time drinking tea in gers, chatting with local yak herders who spoke Kazak and Mongolian, and wandering the hills.