L28 Idles at Railway Platform

L28 Idles at Railway Platform |

Don't take the L-train in China.

I'd never heard of the L line before last week when I bought a ticket for an Urumqi/Beijing run. Times when I don't fly between those cities I would normally take a T-train: the T70 now makes the run from Urumqi to Beijing in under 42 hours. But when I was booking my ticket out of Urumqi there weren't any good discounts on flights, there weren't any other train tickets available... and I had no idea what the L signified.

Let me explain the lettering system that China Railways uses:

Train runs between cities in China are usually designated by a string of numbers. For example, the 5801 shuttles slowly between Urumqi and the Kazakhstan border. If those digits are preceded by some letter of the alphabet, this letter gives an indication as to the speed of the train. With no letter, it's sure to be an ordinary, pokey, slow run--as in the case of the 5801.

Hard-sleeper carriage, L28 |

Then I started seeing Z runs and even D runs. (The D stands for dong che zu 动车组, the bullet trains that now run along China's east coast.)

The only ticket I could book out of Urumqi was for a run a few days later on the L28. This was the first time I'd heard of an L-train. I assumed that with the advent of those increasingly faster Z and D lines, the L would be a speedy operation, too. I was mistaken. The L line is the lousy line, the lame line. It's the only lettered run that must be slower than the regular trains. It took me 65 hours to get from Urumqi to Beijing.

L actually stands for ling ke 临客, a run that has no right of way and is shunted off to a side track at every remote rail station.

Even though taking the train here took the better part of three days, I really can't complain. Many fellow passengers were university students being accompanied by relatives to the beginning of a new school year. When I felt like being sociable I had plenty of people to chat with, usually speaking Chinese. My ticket was in a comfortable class--hard-sleeper--in my favorite location in the carriage: upper berth.

In hard-sleeper class there are usually three bunk levels: upper, middle, and lower. Chinese travelers like the top berth least well. This preference is reflected marginally in the ticket prices. On the L28, middle berth costs about one U.S. dollar less than the bottom bunk, top berth is a buck less than bottom. I've heard reasoning (which I do not subscribe to, myself) as to why the top berth is the least desirable: it has the least headroom and is closest to cool air conditioning coming out of the ceiling.

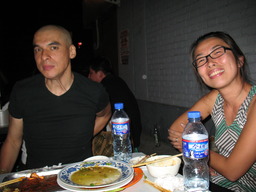

Erik and Lisa |

When the train finally pulled in, I stayed my first two nights in town at Lisa and Erik's hutong apartment. Even though the train arrived past midnight I immediately took advantage of my first Internet access in weeks to place calls to Seattle. I spoke with Mom and Dad for half an hour then responded to messages left by the Census Bureau. Over the weeks I've been incommunicado they had called a couple times to make sure they had my current contact information. They mentioned an operation on which I might be able to find work over October. I think I'll start looking into flights back to Seattle, returning sooner than later.

Everything about Beijing feels so different from Urumqi: 24-hour convenience stores abound, selling alien products such as Pepsi Light. There may be no minority languages (e.g., Uighur) doubling above the Chinese characters on shop signs out here, but English is everywhere--even in the spoken announcements on the city buses and on the metro. An errand that proved a fruitless quest in Urumqi--finding a print shop that could do a thermographic run of my calling card--took a mere 15 minutes after stepping into the first little copy shop I came across. Everything seems easier here.

Maria-João's Birthday at Cafe 'Waiting for Godot' |

Yesterday was Maria-João's birthday. We finished the night up celebrating at a nearby cafe, Waiting for Godot. Walking from dinner to birthday party I recognized none of the area we were in--so was surprised to find I knew exactly where I was once we stepped into the cafe. It turned out to be the very place I had spent an afternoon with Tiffany, over milkshakes, when passing through Beijing last year. Pedro surprised Maria-João with a cake he managed to bake on-the-sly. We lit candles, sang Happy Birthday, sipped drinks, and made conversation. It was a relaxed evening surrounded by new and familiar faces: Lisa and Erik stopped by, as did Rafaella, whom I had met only briefly when she joined us for dinner, back when I was last here two months ago. She was sporting a sharp new haircut, we had a longer chance to converse this time.

Later tonight should be dinner again with the three from Portugal. Maria-João, Pedro, Rafaella, and I have made plans for dinner at Hilal-Ai (Crescent Moon) a Xinjiang restaurant. Even though I've just come from Xinjiang, I'm game. This will probably be my last chance to speak Uighur and to eat Central Asian cuisine before what I anticipate being a long stay in Seattle.